Almanac

Stories. Notes. History.

Stories. Notes. History.

During the XX century Poland has seen a lot of changes and foreign military presence. It has undergone social and economic changes sometimes for better, but on other occasions for worse. Its values have been turned upside down and with that its national heritage. Many associations and individuals have tried to save what was left of heritage buildings on the polish soil in the interwar period and many have succeeded. However, the horrors of WW2 have crumbled down what was salvageable and then the negligence and moods of the communist regime towards the landed gentry and its houses finished it off completely. To put things into perspective, at the end of WW2, before the uprising, the city of Warsaw was damaged but the buildings including palaces and manors were still in some cases able to be rescued. At the end of 1944, after both uprisings, 84% of Warsaw was wiped off the ground. Even greater havoc came after the war with the new communist government, where manors were completely forgotten, and some left to be stripped down and used as a building material for local people. However, in some instances the palaces where decided to be used for official government seats and thanks to this were being renovated, which led to its survival to the 21 century. What we must remember that some of the heritage buildings in Poland have already been badly damaged long before the war, that is during the Swedish deluge which started in 1655. During the deluge most of the castles built in Middle Ages were burned down or destroyed, then soon after some of the buildings couldn’t be sustained by a single family and they went into disrepair.

As we can see polish manors, country houses and palaces as well as castles had a tumultuous timeline of events. Some through the years managed by their own to stand proudly towards more modern times. However, the history didn’t go easy on them. They had to fight their right to be with us today. That is why it is our duty to take care of them now. That is, of protecting our roots as a nation and as each individual. We can only give back to them so little, to help them find purpose in an epoch they were not designed. In the following pages we will share with you some more insight to the world of our shared national heritage, which should be cherished and remembered. We will be sharing our views, stories, inspiration and some history background, for you, on the polish heritage buildings.

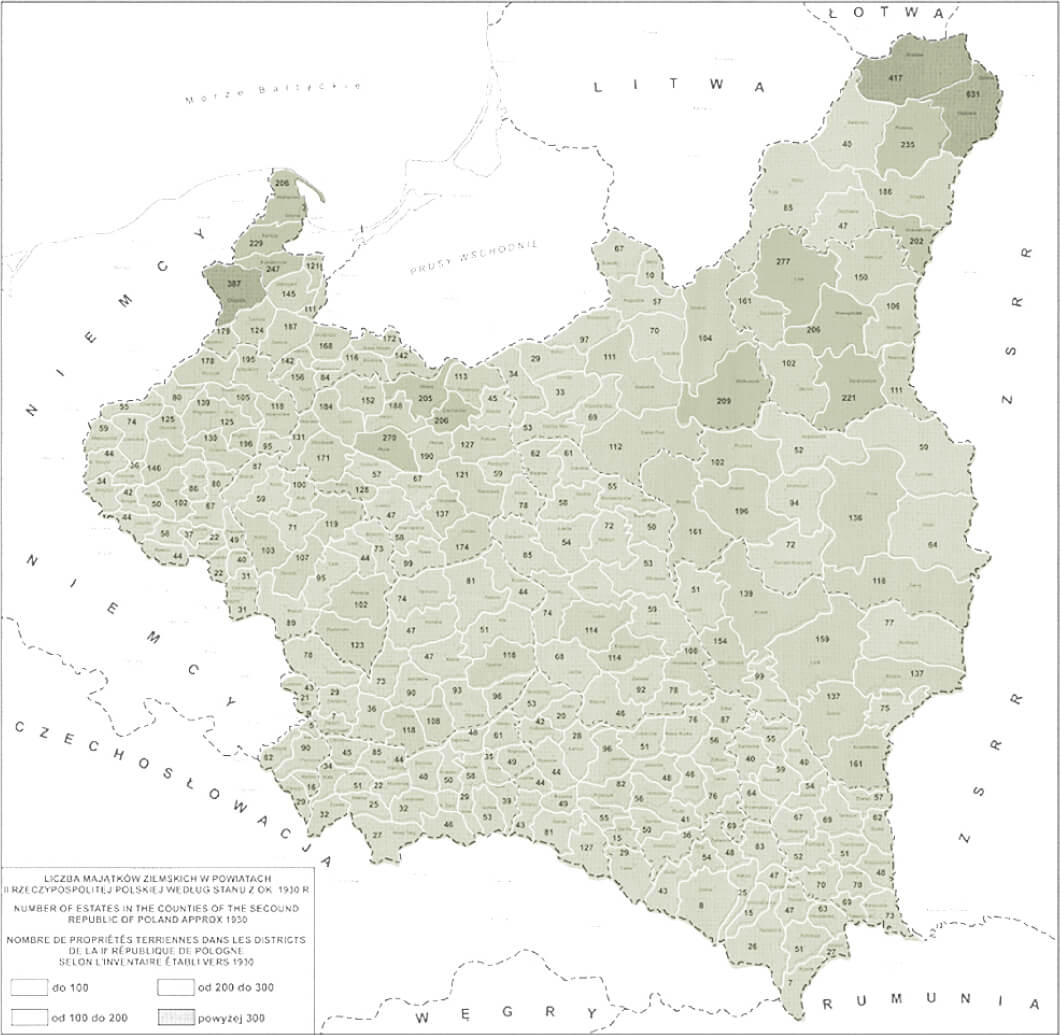

Number of estates in the counties of the second republic of Poland approx. 1930

“History treated the Polish landed gentry in the 20th century rather harshly. First, it was eliminated as a social group. At the same time, and with a great deal of commitment, its material property was destroyed. Then for long decades it was forbidden to write about it, which fact consigned the landed gentry to oblivion and to being effaced from social awareness.” [Tadeusz Epsztein, 2005]

In 1939, there were approximately 16 thousand manors and 5 thousand palaces within the borders of Poland as constituted. Today what is left is only a mere 1% of the 1939 number.

In 1939, there were approximately 16,000 manors and 5,000 palaces within the borders of Poland as constituted. Following the Stalinist Polish Committee of National Liberation (PKWN) decree of 06.09.1944, the state confiscated all estates, livestock, crops, movables such as furniture, paintings, works of art, books and personal effects without compensation. The decree prohibited owners from settling within the district (poviat) of their former properties. 350,000 people were affected by this legislation. Further decrees deprived owners of factories, banks, tenement houses, pharmacies, forests, and securities. Almost a tenth of Poland's population, some 2 million people, lost their property and livelihoods. The agricultural reform in Poland had a political, not economic, purpose. The aim was to destroy the Polish landed gentry, a patriotic and often highly educated class resistant to the Sovietisation of the country. The reform undermined the legal and social order based on the right of property ownership. Following the end of communism in 1989, some mansions were successfully reclaimed by their pre-war owners, despite the Polish state’s reluctance. Owners were either compelled to buy them back or regain them through litigation at the European Court.

In 2013, the Registry of Objects of Cultural Heritage listed 2,700 manors and 2,000 palaces. 3,700 were in ruins, undergoing radical reconstruction or had been totally stripped of assets. Deprived of land, buildings loose their economic infrastructure and viability. 160 manors and 80 palaces remain in their original architectural state, a little over 1 percent of the prewar inventory. However, none survived the communist period with its economic infrastructure intact. The Polish Parliament has yet to pass re-privatisation legislation, making Poland the only EU country in which property rights are not respected. The war time Stalinist decrees are still in force in Poland.

Approximately 1,000 manors and palaces could still be saved.

Landowners lived in their residences (called manors or palaces), which were surrounded with parks. A symbol of the landed gentry, the manor had always been regarded as inseparably connected with that social class. At the same time it was also lastingly connected with Polish culture, landscape, and history. Dating back to the 18th or 19th century, vast majority of the residences had been used for generations. They were enlarged and modernised when needed or when the trends changed. The manor was a family nest and a symbol of the continuity and strength of Polish tradition. Almost every residence housed valuable antiques and works of art. A series of family portraits was a must. Hanging on the walls in the dining or living room, it was a proof of the family’s long history. The portraits highlighted the services of the family members who had held important positions or had participated in significant historic events.

In 1921 Poland there were approx. 19,000 granges over 123 ac, encompassing approx. 28,000,000 ac of land (30 per cent of their total area). The average area of an estate was approx. 1500 ac. Polish interwar agriculture was in debt for many reasons: the destruction of estates during World War I, the low profitability of agricultural production, and the Depression during 1929–1933. Some estates were poorly managed and their owners did not invest in their development. Moreover, the tax rates for vast estates were higher than for small farms. The many landed gentry who were in arrears with their taxes for the State Treasury were forced to parcel out their estates. The steps taken by the government, such as the debt restructuring act, and the upturn in the economy improved the situation of landed gentry just before the outbreak of World War II.

In 1921 Poland there were approx. 19,000 granges over 123 ac, encompassing approx. 28,000,000 ac of land (30 per cent of their total area). The average area of an estate was approx. 1500 ac. Polish interwar agriculture was in debt for many reasons: the destruction of estates during World War I, the low profitability of agricultural production, and the Depression during 1929–1933. Some estates were poorly managed and their owners did not invest in their development. Moreover, the tax rates for vast estates were higher than for small farms. The many landed gentry who were in arrears with their taxes for the State Treasury were forced to parcel out their estates. The steps taken by the government, such as the debt restructuring act, and the upturn in the economy improved the situation of landed gentry just before the outbreak of World War II.

Despite being perceived as a homogenous group from the outside, the landed gentry were highly diverse. At the top of the social hierarchy was the aristocracy—a very narrow, hermetic group, which successfully defended its status. It was composed of a few dozen of the most well-known families with historic surnames and aristocratic titles, usually of counts (hrabia) or princes (książę). Most of them were from noble families that held important public positions in the First Republic of Poland. Later on they were joined by families that achieved a high social and material status in the 19th century.

Aristocrats possessed many vast estates in various parts of the country and magnificent historic residences, for instance, in Głochów, Kozłówka, Łańcut, Nieborów, Nieśwież, and Sławuta. They invested their savings in shares of banks and industrial companies. The aristocrats’ standard of living was very high: they often travelled abroad, pursued careers in politics, and collected works ofart. The aristocracy married exclusively with members from their own social class, which prevented outsiders from entering it. Moreover, aristocrats were often connected by marriage with the ruling families.

The information and texts included on this page are shared with you from the the exhibition “Europe in the Family. The Polish landed gentry in the 20th century”, prepared by the Institute of National Remembrance [Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, IPN] and the Polish Landowners’ Association [Polskie Towarzystwo Ziemiańskie, PTZ], tells about the history of the Polish landed gentry and its fate in the 20th century.

Social life was an element of the landowning culture. From an early age every child spent time in a large group of people, learning good manners and the art of conversation. The landed gentry regularly met with residents from the neighbouring manors and invited the local intelligentsia, officials, officers from the local military units, and members of the clergy. During meetings, the people talked about agricultural issues, exchanged news from the world of politics, played cards (particularly bridge) or the piano, rode on horseback, did sports, strolled in the park, and organised picnics in summer. During carnival the landed gentry organised balls or evening dance parties. Holidays and any family occasions, such as weddings, baptisms, and funerals were especially celebrated. Likewise, Christmas and Easter were celebrated in style and in large groups of people. Great importance was attached to food and meals, which were celebrated like rituals—they lasted for hours and consisted of many courses. Many manor owners kept guest books, where their guests could praise their hospitality and the atmosphere in their residence.